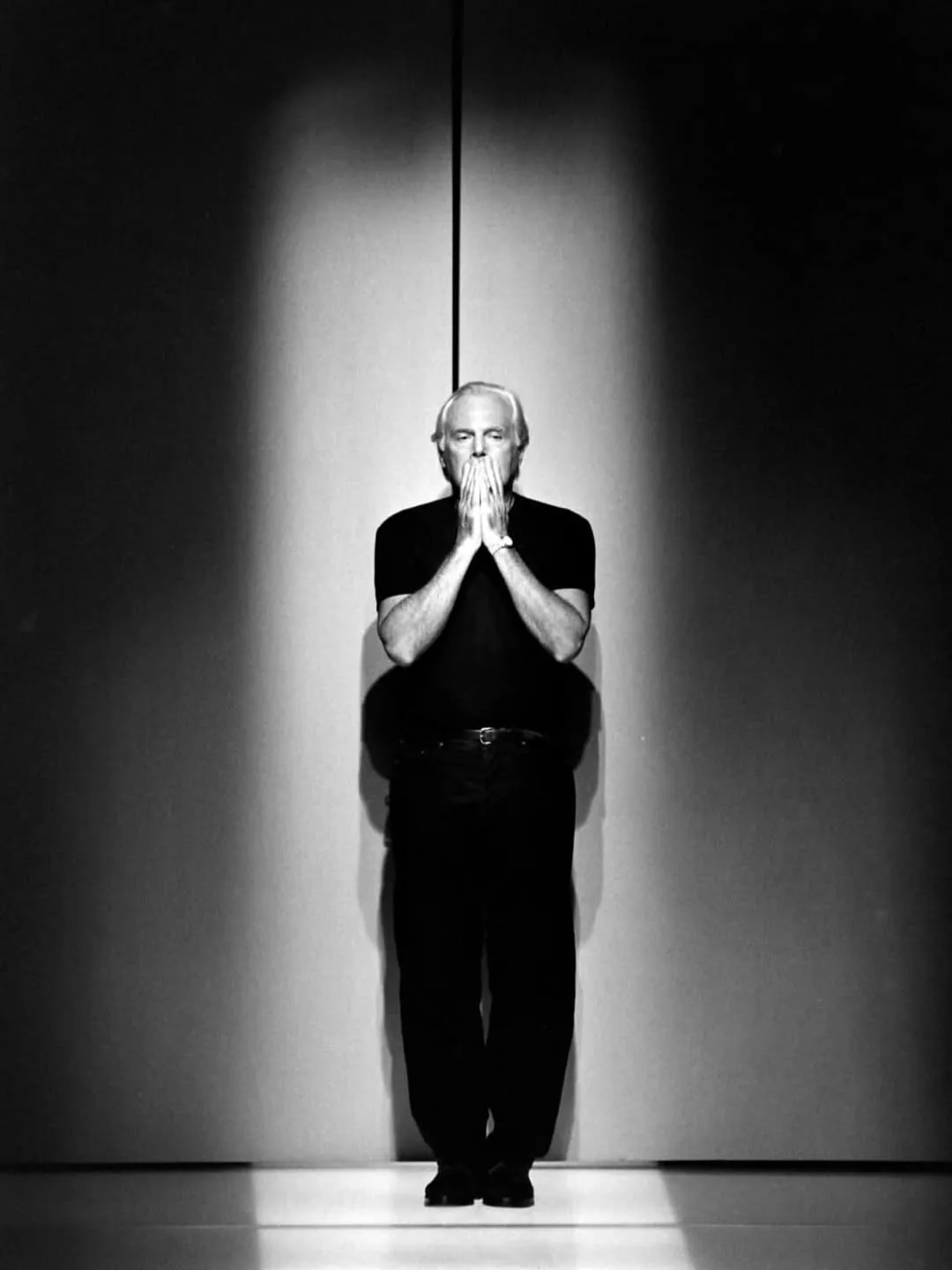

Giorgio Armani: An Intimate Reflection On His 50-Year Legacy

Less than a year before his passing, Osman Ahmed interviewed Mr Armani for Harper’s Bazaar Arabia – a poignant reflection on his sensational half century in industry, and the innovations he was still championing with a very modern mind

When I meet Mr. Armani – never Giorgio, even to those in his inner sanctum – on the eve of his 90th birthday this past summer, he is at home in Milan, surveying his light-dappled Japanese garden as construction work takes place. Though he is smaller than you might think, it’s here that the portrait of the man behind the myth, one of fashion’s last eponymous titans, reaches full scale. “I love being at home. It’s my safe, placid space,” he tells me via a translator. “The biggest misconception about me is that I am cold and distant. In truth, I am a shy person who cherishes affection from a close circle of loved ones.”

This month, far from Mr. Armani’s Milan address, Armani is opening a new 12-storey limestone building on Madison Avenue that he helped develop. It will have 10 luxury condos above a Casa/Armani store, a flagship Giorgio Armani boutique, and even a restaurant. “Somehow, I have turned my fantasy of being a movie director into reality,” the designer says, laughing. “First, I dressed the characters, then I gave them furniture, a house, then flowers, restaurants, sweets, and so much more.”

To celebrate the occasion, Armani’s Spring 2025 runway show will take place in New York City, marking the first time that the designer has shown his main collection outside of Milan. In addition to feting the new building, Mr. Armani explains that the move is a gesture of gratitude: “America, and New York in particular, is where I found my first real audience – a whole generation of men and women eager to represent themselves in a new way,” he says. “Women in particular were taking strides in the workplace and needed a modern approach to dressing. What I like about the American audience is how open it is to new proposals and [also] its loyalty.”

The Armani suit started it all. That was the thing that first opened the front door to the Armaniverse on a global scale. Back in the 1970s, Armani’s two-piece tailoring ushered in a new kind of power dressing: low-key and unadorned, assertive in its purposeful use of menswear fabrics, sensually supple against the skin. Armani armoured a generation of women climbing the corporate ladder in relaxed, unstructured suits. The look was seen on everyone from Richard Gere in 1980’s American Gigolo to Jean-Michel Basquiat, who famously painted in Armani suits, to Grace Jones for her 1981 Nightclubbing album cover. Long before gender was a hot topic, Armani toyed with its sartorial associations to subtly expand its parameters. His advertising imagery, often photographed by Peter Lindbergh and Aldo Fallai, cinematically framed the Armani man and woman as modern-day Italian neorealist heroes navigating the world together in black and white.

“Every chic woman who was finally wearing a pantsuit wanted it, every banker wanted it, every good-looking actor wanted it,” says Elizabeth Saltzman, who began her career in 1984 in the Armani publicity department in New York City and then went on to become one of Hollywood’s first celebrity stylists, with clients such as Gwyneth Paltrow, Uma Thurman, and Sandra Oh. At the time, she adds, Armani offered a uniform that announced quiet confidence for both society doyennes like Lee Radziwill, who was in search of a breather from beading and taffeta, and a new generation of upwardly mobile professionals.

“If you wore Armani as a man, you were taken seriously,” Elizabeth explains. “If you were a woman, you were in a boy’s suit, but you couldn’t have been more feminine because it was fluid and in a softer palette than fashion at the time. You could throw it on and feel powerful, which women needed because they were stepping into powerful positions.”

A younger generation of actresses is looking to Armani lately, perhaps as a riposte to the gilded, over-the-top redcarpet looks that seem to get bigger and bolder each year. In May, Hunter Schafer stepped onto the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival wearing a custom-made iteration of a Spring 2011 Armani Privé gown, an iridescent silk-organza creation that fl owed around her body like ice-blue liquid mercury. It was, in fact, silk woven with metal to achieve a refl ective glazed surface – and it landed her on every bestdressed list. “It’s smart, easy, effortless, not too fussy – everybody wants to look like that right now,” enthuses Dara, the stylist behind Hunter’s red-carpet hits. “My dad’s Armani [reference] was Richard Gere; mine is Lady Gaga in Armani at the Grammys in 2010.” She adds, “There’s something so magical about that period of Armani for me; it just conjures such a fantasy of the future, and I wanted to reinterpret that for the kids.”

Stars like Hunter aren’t the only ones flocking to Armani right now. The tailoring, in particular, is soaring in demand after years of sportswear dominating the catwalks. According to the luxury-resale platform Vestiaire Collective, searches for vintage Armani have gone up by 50 per cent so far this year alone. Perhaps the similarities between then and now – socioeconomic extremes, a rapidly changing media landscape, geopolitical uncertainty, the return of hedonism – explain why so many other designers are revisiting Armani’s earlier work as some kind of salve for turbulent times.

“One thing I have learned in my 50-year career,” Mr. Armani reflects, “[is that] fashion is cyclical, and ideas that got the spirit of the time are the ones most likely to make a comeback. After the overload of loud fashion, the younger generations have rediscovered my work, and I can’t deny this makes me proud.”

Mr. Armani is one of a select group of legendary designers who have shaped the way women have dressed over the past century, and within that group, there have been eclectic approaches to the job at hand. Some have been technical geniuses, searching deeper between the seams to innovate new forms of dressmaking. Others have constantly been in a state of transience, traveling from idea to idea in search of inspiration. Some have questioned the very nature of luxury, deconstructing it in search of modernity, while others have seen bodies as canvases for flights of fantasy, or living artworks. For Mr. Armani, it has always been about the pursuit of timelessness.

After five decades in business, one that’s now worth billions, the self-trained designer knows exactly what he likes and is still involved in the day-to-day, nine-to-five-and-beyond workings of his brand. He follows a strict daily routine that starts with a morning workout in his home gym: a mirrored room with framed pictures of family, as well as himself topless in his athletic prime and four feet high on the cover of Time magazine in 1982. In the evenings, he relaxes in a simple armchair decorated with pillows and a cotton throw blanket, watching Netflix or a movie. Some of his recent favourites include The Crown, All Quiet on the Western Front, and The Zone of Interest.

Mr. Armani pioneered the idea of building not just a fashion label but a world – a place to dress and live, one realised in his own personal Peter Marino–designed living quarters in Milan. These spaces are decorated with Japanese antiques, lacquered bookshelves, and hand-painted Chinese screens. There is also a private cinema resembling a neutral-hued spaceship with an ornate fresco on the ceiling. Each room is a distillation of Armani’s unwavering design philosophy: elegantly unfussy, pure in the Eastern sense rather than capital-M minimalist, grandeur with the casual ease of Italian sprezzatura.

Now entering his 10th decade, the designer has often batted away the idea of a successor. There are, nonetheless, designers he admires: Miuccia Prada and Hedi Slimane, with whom he corresponds via handwritten letters; Stefano Pilati and Dries Van Noten; and, Rick Owens, the only one he mentions to me by name. “I admire creators who stick to their guns and focus on clothes rather than communication,” he elucidates.

Rick Owens, upon hearing his admiration, returns the favour: “Some might be surprised to know how closely I have followed Armani’s lead,” he writes by email. “His world of languid 1930s dignity in beige and gray wool crepe framed in travertine Italian rationalist architecture, seen through a 1980s filter, was such an blueprint for me to follow in my own way.”

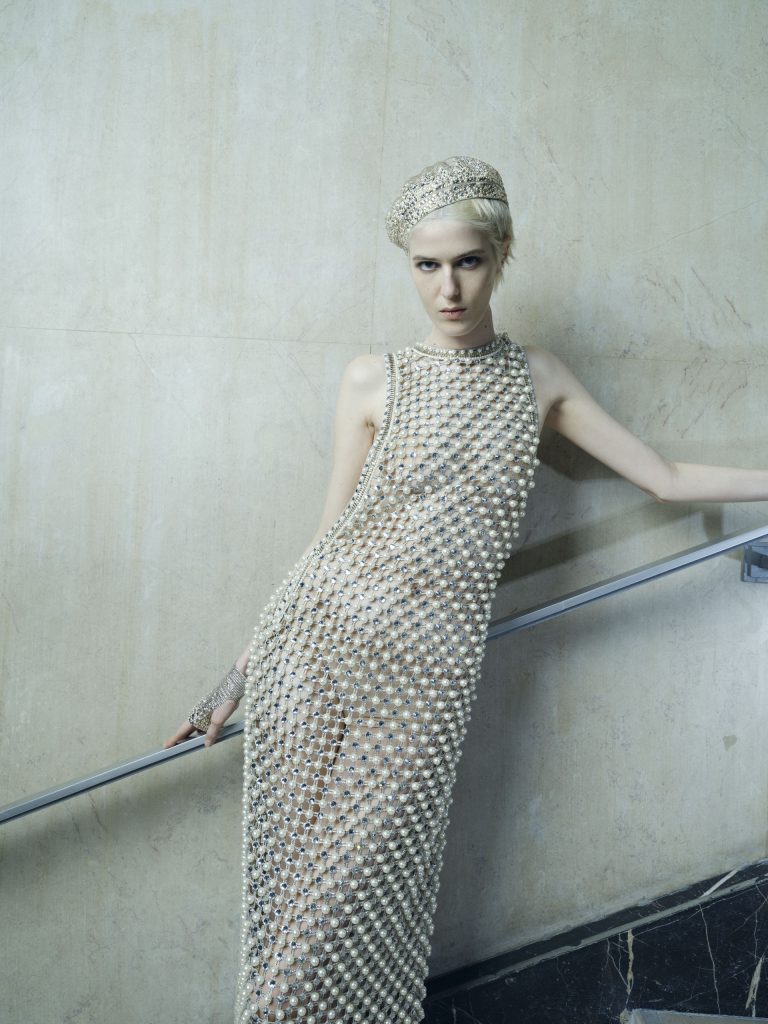

What Armani represents in today’s frenetic fashion landscape is consistency. For him, evolution in design is measured in the merest millimeters and the subtle nuances of neutral hues, as evidenced by his Autumn 2024 haute couture collection, which riffed on his signature champagne-colored gowns and slim-cut, soigné tailoring. “I have always believed in evolution rather than constant and excessive revolution,” he says. “My work revolves around a well-defined edit of shapes and silhouettes, which I endlessly explore and improve, season after season, following times that change and customers that evolve. Women today are not afraid of glamour, even in the workplace, and that is reflected in what I do.” Though traditional, the approach feels refreshing at a time when fashion houses have revolving doors of creative directors; Armani remains at its Armani-est because, well, it still has Mr. Armani at the helm.

There’s also the fact that Mr. Armani practically invented the idea of red carpet dressing and continues to be a consistent presence there, even as the rules have changed dramatically. The legend goes that when he opened a store on Rodeo Drive in 1988, he hired fashion journalist Wanda McDaniel to dress actors for awards ceremonies and movie premieres. Back then, stars didn’t have stylists, let alone glam squads. Armani arrived in town to deflate the satin puff balls and bows that dominated ’80s eveningwear, offering actors a cleaner, sleeker look. In 1990, Armani dressed so many stars at the Academy Awards that Women’s Wear Daily ran an article headlined “The Armani Awards,” citing Armani-clad stars including Michelle Pfeiffer, Kim Basinger, Robert De Niro, Steven Spielberg, Julia Roberts, Denzel Washington, Jodie Foster, Steve Martin, Tom Cruise, Jeff Goldblum, and Dennis Hopper, to name just a few. Since then, Armani has been worn more than 500 times to the Oscars alone, and it is considered the “luckiest” designer to wear, considering the number of award winners clutching gold statuettes in their Armani outfits.

“Working with the stars back in those days was quite easy, a mutual encounter between young actors looking for new ways to dress and a designer, me, keen on modern dressing,” Mr. Armani says with a sigh. “I was an outsider at first, but I was able to build real and lasting friendships with many stars. Today the workflow is different.”

“I purchased an Armani suit with my first pay cheque as an actor,” says Cate Blanchett, who responds instantly when I inquire about her longstanding relationship with Mr. Armani. That gray checked pantsuit is still in rotation. Cate has worn Armani countless times, on and off screen, but her favourite is a backless black lace gown he made for her for the 2014 Golden Globes, which she wore two more times on the red carpet, eventually repurposing lace off -cuts from the dress into another Armani gown. “He is a renaissance man,” she says of the designer. “Well-versed on so many subjects, from sustainability to Doric columns to chocolates. He is a serious person who prizes authenticity but always has a twinkle in his eye.”

Above his desk in his home office, which looks out onto a pagoda filled with bonsai trees, hangs a painting by Silvio Pasotti that depicts some of 20th-century fashion’s brightest stars: Christian Dior, Elsa Schiaparelli, Yves Saint Laurent, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Gabrielle Chanel, Madame Grès, and Karl Lagerfeld, to name a few (as well as Mr. Armani, of course; he commissioned the artwork). It offers insight into how he views himself within a generation of designers for whom an unwavering signature was not just a calling card for clients but a tool for a self-mythologising legacy. What will Mr. Armani’s self-fulfilling legacy be? The tailored suits that armoured a generation of women striding into the workplace? The unstructured menswear that softened the image of masculinity? The hotels, beach clubs, furniture, or fragrances? The Oscar-winning gowns and tuxedos? The designer hopes to be remembered for something far more than just a piece of clothing: the lifestyle to live in the clothes. “Being remembered would be an achievement already,” he demurs. “Being remembered as the inventor of an effortless and timeless style would be the coronation of it all.”

Lead image courtesy of Instagram / @giorgioarmani

From Harper’s Bazaar Arabia’s December 2024 Issue