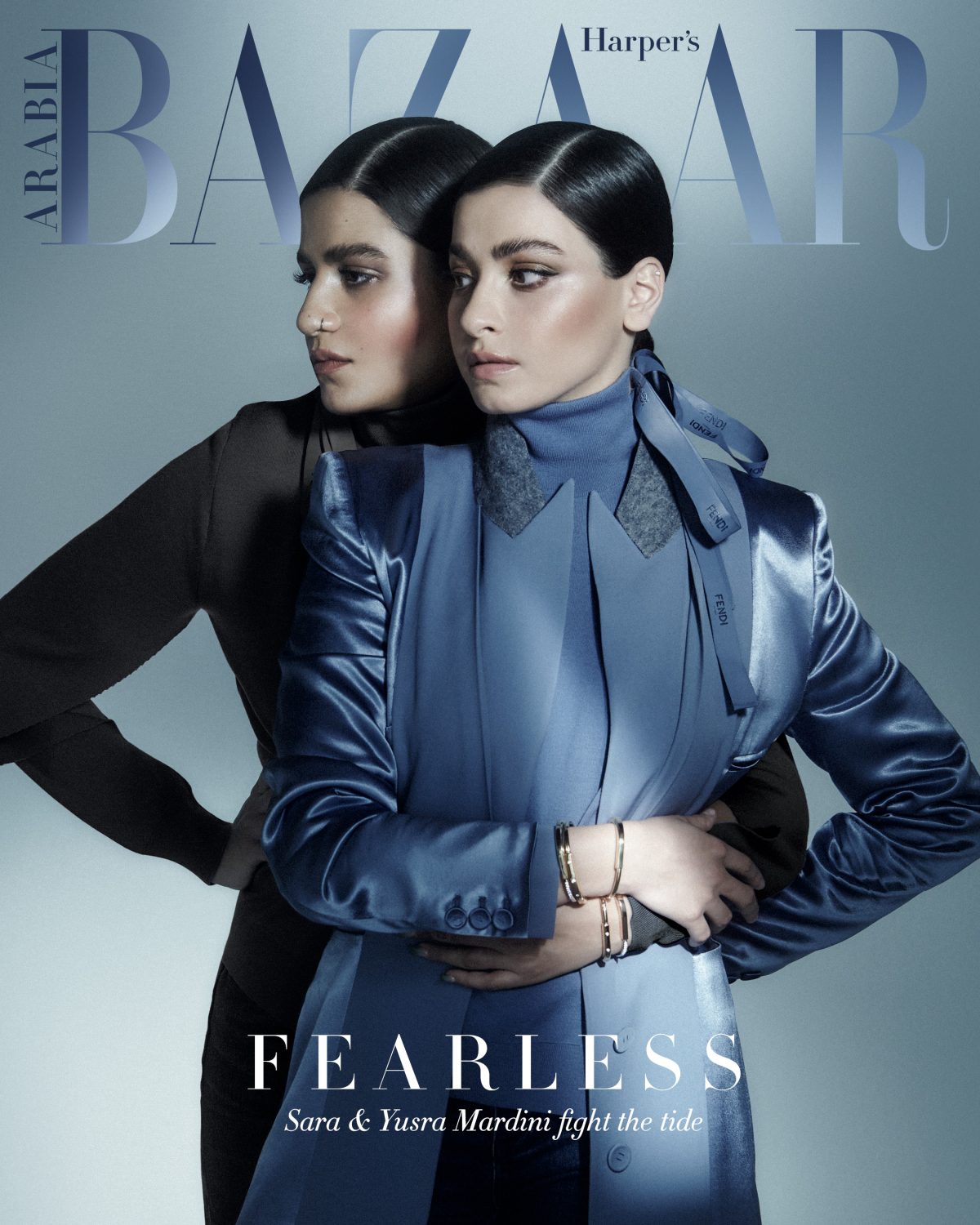

Sisters Sara and Yusra Mardini On The Swimmers, Survival, and Their Syrian Roots

Extraordinary sisters Sara and Yusra Mardini fled devastated Damascus to find freedom. With it came unexpected fame, Olympic glory and even a film chronicling their heroic, life-saving journey. The story, however, is far from over…

There are 30 million refugees worldwide, and half of them are under 18. Those are the sobering statistics that you’re left with after watching Netflix’s The Swimmers, a tale that chronicles the 2015 crossing of Sara, then 20, and her 17-year-old sister Yusra Mardini, two of the 5.7 million Syrian refugees who have been forced to leave their home to travel to safety, since 2011.

When their house was destroyed and an unexploded bomb landed in the pool where Yusra was training, the sisters knew they had no choice. They left their family aiming to get to Europe so that the rest of their close-knit clan could get safe passage, away from war-torn Damascus. Their perilous journey via Lebanon, Turkey, Greece and the Balkans was filled with danger but the two were relentless, eventually reaching Berlin after 25 days.

They also became unexpected heroes when, en route, their dinghy – which should have only carried eight people – was overcrowded, causing the motor to fail while in the middle of the Aegean Sea. The girls, who were trained swimmers, jumped into the water, and with two others, swam for over three hours to Lesbos, pulling the sinking boat and saving 18 others on board.

The fact that Yusra, who had been coached by her father since she was a child, achieved her dream of participating in the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics as part of the first Refugee Olympic Team seems to suggest that on the surface this is a story with a happily ever after ending. But dig a little deeper and you’ll understand that that’s a simplistic synopsis of a deeply traumatic experience, and one that hasn’t found its conclusion quite yet.

Riding the tide

While watching the movie, the viewer goes through a gamut of emotions – it is harrowing, uplifting, tragic and joyful at the same time. Its success lies in its universality – there are aspects to it that you can’t help but relate to, as it touches everyone. While speaking to Sara and Yusra, you realise that they might have become poster girls for the refugee cause, meeting everyone from Pope Francis to Barack Obama – and that they’re happy to carry that mantle – but it certainly wasn’t the plan.

“Honestly it wasn’t our idea,” explains Yusra, now 24, when asked about how the movie came about. “We tried to cross, we tried to survive. We just wanted to live in peace again after we crossed. But when we got to Germany there was a lot of media attention after I went to the Olympics, and with Sara volunteering.”

She continues, “The first idea was to bring a book out [2018’s Butterfly: From Refugee to Olympian – My Story of Rescue, Hope, and Triumph] and after we wrote the book, lots of production companies contacted us. There was this one producer, Ali Jaafar, who was always texting, really persevering, so we were like: ‘Let’s give him a chance.’ We watched one of his movies, The Idol, about the Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf and were really impressed. After that we talked to Working Title, felt comfortable and that was it.”

Sense of purpose

The movie doesn’t purport to be a documentary, but uses the girls’ lives as a base to weave in other elements. “Of course you have different stories of different refugees but at the end of the day, the journey is the same,” Sara explains. “Looking for safety and leaving your home behind. So I think Sally [El Hosaini, the director] did a really great job researching all the different crossings and then trying to represent them in our own story.”

Were there any non-negotiables that the Mardinis felt had to be represented? “We wanted it to be as authentic as possible,” Yusra passionately states. “We knew that there would be elements of fiction but we really wanted our authentic story to be out there. In the end they are talking about us. It is our life story. We weren’t fans of it being fictionalised – that is what I was personally scared about. When we watched it, it was just very, very good. Even if the situation did not happen exactly the way it is depicted, it did happen, or it did happen to other refugees and that was the main point.”

“For example, in the movie you can see that our cousin got depressed, you can see there was push back when the woman and her baby had to go back to Eritrea, you see sexual harassment – it didn’t actually happen to me but it happened to many, many women crossing. I think it was all portrayed really, really beautifully.”

Yusra was always confident that her tale would be one that would be embraced: “Honestly, I absolutely knew, 100 per cent. That was the point of sharing our story, with all its personal details. We wanted to make the movie because we knew that lots of refugees don’t even have the courage to tell their stories because they are scared of people not believing them. We realised we had a strong story. Why not tell ours and make it a movie too?”

Divergent journeys

You see the very different characters of the girls in the movie – Sara, boisterous, impulsive and fun-loving, while younger sister Yusra is more keen to keep to the straight and narrow, to toe the line. And in person, their differing personalities are also apparent. Therefore it isn’t at all surprising that a similar starting point has taken them in distinct, divergent directions.

If you’re looking for closure and a neat finish, this multi-layered saga doesn’t tick all the boxes. When I comment that it feels like their trials never stop, Sara intercedes, wryly commenting that: “Yeah, but in my case this hasn’t started yet.”

What she is referring to are the criminal charges levied against her for smuggling, espionage and fraud in Greece. Sara decided to go back to Lesbos with an NGO to help other refugees by using her language skills, but in 2018 she was arrested along with other members of the group. She is currently released on bail and is with her family in Berlin, but if found guilty could face a prison sentence of up to 20 years.

“It has been ongoing for four years. I am banned from Greece so I have to wait for permission to be granted to return. If they allow me to testify then I will go to court on the 10th of January.” Human Rights Watch has categorically refuted the charges, supporting her innocence by releasing a statement saying that “The slipshod investigation and absurd charges, including espionage, against people engaged in lifesaving work, reek of politically motivated prosecution.” Amnesty International has called them “unfair and baseless.”

Stepping onto the world stage

After arriving in Berlin in 2015, determined Yusra sought out the local swimming club, convincing Sven Spannekrebs to coach her. The partnership resulted in her participating in the Rio Olympics – her goal from the get-go – earlier than anticipated, as everyone felt that Tokyo 2020 was a more realistic target. She ended up winning her 100m butterfly heat, ranking 41st out of 45 competitors.

Yet Yusra still took some convincing at the time, as she felt uncomfortable with the word ‘refugee’ and still wanted to represent her own country, Syria. She sighs as she thinks back, “I was very, very young when I got to Germany. I struggled with the term. For so many people around the world ‘refugee’ means you are poor, you dress badly, you live in tents, they don’t know a lot about us. At that moment I was afraid of people labelling me and thinking I wasn’t educated,” she shares.

“I also struggled with becoming a part of the Refugee Olympic team because I didn’t want people to say: ‘Oh, she is here because she became a refugee and that made it easier for her to participate.’ Never in a million years did I think there would be a Refugee Olympic team. I wanted to qualify for Syria. I wanted to earn my spot fair and square. My story isn’t who I am. What happened to me doesn’t define what happened next. At 17 it was hard for me to say that I am a refugee and proud of it.

“I was so young and couldn’t come to terms with having to start from zero again. You don’t really grow up in the Arab world being educated about the refugee situation to be honest. Around the world people don’t really know why refugees choose these paths. There are millions who leave everything behind. When you come to Europe, you get to the point that you can live a good life. Why not? You are contributing to society. It is fine to dream. It is fine to want to be a top athlete. But this is my mentality now, over seven years after I first left home. Then, I was so frustrated. People knew so little about our life in Syria. They asked me things like, ‘Did you have a racing suit? Did you carry an iPhone?’ I was like: ‘It is one of the oldest capitals in the world, one of the oldest countries in the world…’ That was frustrating.”

Reliving their crossing

Sneaking through borders requires you literally putting your lives in the hands of complete strangers who are in it just for the money. “You are choosing to trust someone you’ve never seen before – the smugglers – you are gambling with your life. You are choosing to trust people around you that you’ve never met. You have to be so spontaneous. So trusting. Otherwise you won’t make it. I was 17 at the time and I didn’t understand what I had done to have to take this journey,” says Yusra.

And as it turned out, the Mardinis’ faith in their filmmakers turned out to be well-founded. “We saw the final cut before it was released. Me, Yusra and Sven watched it together here in Berlin,” Sara recalled. “I remember I was crying from the beginning till the end. You try to imagine what it will be like but it is completely different when you see it. We were blown away. We were so happy with it. We were really impressed by it.” Yusra adds, laughing, “I didn’t have any comments and that is very rare as I always have opinions!”

Sharing the spotlight

There’s a scene in the movie where a character calls Sara a superhero. When subsequently musing over what both Sara and Yusra have gone on to achieve, that strikes a chord. It shows that role models don’t necessarily have to follow the stereotype of success. What might not garner the headlines or create the same feel-good factor, might be just as heroic. And there must be an equal emphasis on both their achievements.

Sara bats away the compliment, “I don’t see myself that way. I just see myself as someone who’s capable of giving back and that is why I went back to Greece. I thought I could offer something there. It was a passion for me just to be there for other people. And I agree that the movie offered respect to both our lifestyles and choices.” Yusra chimes in: “It was interesting how the media made it sound. They sometimes phrased it like: ‘Yusra and her sister.’ They wanted to focus on the Olympics, they wanted [the narrative] to go ‘from being a refugee to an Olympian’, which wasn’t true! I have been a swimmer – an athlete – my whole life. Some people didn’t even realise that I had been swimming in Syria, that I had been to the World Championships.”

And although it could have been simpler to just focus on Yusra, that was never an option: “For Sara, Sven and myself, it was always about the sisters’ story,” clarifies Yusra. “Whenever I told the story, it was always my story and my sister’s story. It was never just mine. Sara was always involved. She came to the screening with me, to the first meetings – the whole family were there – so it was very obvious that it was a story about my whole family but focusing on me and my sister.”

Striking a chord

Although their personal paths may have taken them to different continents, as Yusra is currently studying film and television production at the University of Southern California, while Sara is with the rest of her family in Berlin, it’s clear that their sisterly bond, which carried them through the darkest part of their lives, remains strong.

That is probably the most poignant, and relatable aspect of their story. The actresses who portrayed them, Lebanese duo Nathalie and Manal Issa, who also left their homeland to live in France, channel their relationship beautifully.

“They are sisters so you can see that bond. I don’t think it was easy for them to play those roles, especially as it is about real people. Usually when you do this kind of a movie, the person is either 90 years old or has passed away. You wouldn’t expect someone to be around, still in their 20s. Both of them went through a lot as well. They are Lebanese so they understand why we chose to leave and some of the struggles that we had. I think both of them did a great job,” says Yusra.

Warming to the theme, Yusra feels that “people can relate to so many things in the movie, even if they are not refugees. You can relate to being an athlete, to being a mother, to having this bond with your family, to being the little sibling. That is a great way to connect. I think the story was portrayed in a different light from how refugees are usually portrayed in the media. Of course we struggled, of course we were sad, but we didn’t lose our hope. We didn’t give up. We were still laughing and smiling. That is completely true. Even if you go through something traumatic, you can choose to continue and ask for help.”

A stalemate on the situation

Hearing about their crossing, you feel like they had a relentless array of challenges. “There wasn’t a specific moment that I wanted to go back but it was difficult at every border,” Sara recalls. “When we arrived in Hungary it was very difficult because we were stuck there for 10 days. The conditions were not good. The locals were not happy with us. It was an intense situation. There were no smugglers or anything and it was really frustrating to be stuck in one place for so long. You really didn’t want to be there.”

Campaigning for change is at the heart of the sisters’ mission now. Yusra passionately asks: “How bad was it in Syria for people around my age to be crossing this way? Why isn’t there a system to be able to cross safely? If you’re European for example, you can just move to the next European safe country if something like this happens, and I was wondering why they can’t do that in the Arabic world? We should have the same bond.”

The twosome also defy a lot of stereotypes. They led a happy, solid middle-class life in Syria – something that is clearly depicted in the movie – but because they were refugees, they were considered ‘other’.

“I think, in general, people forget the fact that refugees had jobs and lives back home. They are doctors and teachers, farmers… but the fact that most refugees come from countries people don’t know much about – most people didn’t know anything about Syria before the war started – people coming from a different place means we categorise or box them in a way,” explains Sara. “Of course many of them don’t have money while crossing as they’ve lost everything back home. They are living in a war. People make it because of savings – they use everything they have. These judgements come about because people don’t have conversations. They don’t know why they lost everything.”

Despite all this, they yearn to go back to their motherland. “Of course, I love Syria. It is my country in the end. We had never thought of leaving. We loved our lives there, we loved our friends. You complain about your country but you never think of abandoning it,” Yusra insists. “I don’t know if I can live there again, as it would again be starting from zero – I want to go back and just enjoy the country. The war has gone on way too long…”

Looking ahead

After the whirlwind of a red-carpet publicity tour – The Swimmers premiered at the 2022 Toronto Film Festival’s opening gala – countless interviews and “our first Arabic magazine cover” for Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, you’d think these two dynamic young ladies would be content to rest on their laurels.

But there’s no chance of that. “I am currently campaigning for my trial,” Sara tells us, brightening up when she maps out what she hopes is in store: “In the future I would like to go back to school to study fashion or fine art but at the moment I am busy with my case so I cannot do much until I am proven innocent.”

Alongside her studies, Yusra, who was appointed the youngest UNHCR Goodwill Ambassador in 2017, is due to launch her new foundation in 2023, simultaneously in both the US and Germany. “We are enjoying the release of the movie and doing a lot of press around it. I also got my German passport. It has been an eventful year,” she laughs. Lastly, do the two think they would have completed this journey if they hadn’t been such strong swimmers?

For once, there is a difference in opinion. “I don’t think so,” is Sara’s immediate response. Simultaneously Yusra chimes in with, “I think so.” “But we would not have made it through the water… The decision-making would have been different. My mum was very scared, but we were confident nothing would happen in the water. I mean something happened, but we were able to manage it. We wouldn’t have left Syria if we hadn’t been sure,” counters Sara.

“You volunteered because you were brave. In my opinion, yes we would have made it because we are very stubborn. We wouldn’t have given up so easily. It may have been way crazier. But knowing you, Sara, I think you would have jumped in the water,” Yusra insists. After learning about all they’ve conquered through sheer grit and determination, we can’t help but agree with her.

Photography: Jonathan Segade. Styling: Anna Castan

Editor In Chief: Olivia Phillips. Art Director: Oscar Yáñez. Senior Producer: Steff

Hawker. Hair: Eduardo Bravo. Make-up: Alisonn Fetouaki. Photographer’s Assistant:

Daniel Caparros.

From Harper’s Bazaar Arabia’s January 2023 issue.